|

The following are notes based on a talk given by my teacher, Dr. Arnaud Versluys, Founder and Managing Director of the Institute of Classics in East Asian Medicine. The topics covered here are often brought up when discussing the rich history and fundamental principles of Chinese Medicine with patients and Western medicine colleagues. Each point below can be understood on its own, as they are taken out of a larger discussion for the sake of simplicity here.

0 Comments

The Shang Dynasty is the earliest empire in recorded Chinese history, of which there exists some archeological evidence. The first, possibly mythical, dynasty in Chinese history that came before the Shang was the Xia Dynasty. The Shang Dynasty lasted from about 1766 - 1027 B.C., give or take a few years, of course. The Shang ruled in northern China, with their kingdom situated along the Huang He, Yellow River.

During this time, the first writing system was developed, in which pictographic and ideographic characters were inscribed into bones. These bones also play a central role in the medical system of the time, as will be discussed shortly. The Shang society is said to have produced the earliest known evidence of both the prevention and treatment of illness to be found within Chinese culture. The Shang were ruled by a centralized king, and the majority of all other citizens were peasants who lived in the small rural towns outside of the capital. Daily life was occupied by livestock maintenance and agricultural work. Although they were considered to be beneath the king, each member of society held a specific role and attempted to maintain the integrity of the whole to the best of their ability. The only members of society whose status was superior to even the king were the deceased ancestors, who were believed to continue to influence the lives of the living even after they were physically gone. The most important ancestor was Ti. Ti was the reason for the changing of the seasons, and also for good and bad fortune. It was the king's job to make sure that Ti was pleased, and he did this by communicating with Ti, as well as with his own direct ancestors, through the use of oracle bone divination. The bones of animals, particularly tortoise shells, after having several holes pierced through them, were presented to the king. The king would then make his inquiry or request to the ancestors and expose the bone to heat. This heating would produce cracks in the bones that were interpreted by the king as the will of the ancestors, guiding political and other decisions to be made for the benefit of society. Individual illness, as well as community-wide pandemics and bad luck, were believed to come about whenever Ti or any other ancestor became displeased. The entire community sought to please one another's ancestors to ensure that this did not happen. In early China, sickness was mainly linked to curses brought on by the ancestors, and in order to prevent or cure illness, the Shang king spoke directly to the ancestors on behalf of the afflicted persons. The king was the one and only link to the deceased, making him a healer as well as a leader. Healing was done on a mass scale, and included the entire society as a whole. In addition, sacrifices and offerings of precious items were made to both prevent and counteract illness. Unschuld, Paul U. "Illness and Healing in the Shang Culture." Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1985, pp. 17-28. The image above is written in an ancient East Asian script, with the characters representing the words -- or more accurately, the idea and feeling of -- "great nature." The meaning of these words may seem simple enough to grasp, and after reading it once on a business card, sign, website, or elsewhere, you likely never gave it another moment's thought. That is why I am writing this blog. I'd like to share a bit with you about why I specifically chose this as the name for my Oriental Medicine clinic. Please read on. I think you'll find this short blog intriguing. Much of the information presented here comes directly from the writings of Rev. Koichi Barrish, Senior Shinto Priest of Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America; as well several other print and online sources that will be cited below.

The kanji above is written with two parts -- one of which reads Dai, meaning "great;" and the other reading Shizen, meaning "nature." But, of course it is not quite that simple. "Traditionally, shizen meant 'naturalness' more so than 'nature.' Literally, the meaning is 'from itself (shi) thus it does (zen).' Shi refers to what is spontaneously so. Etymologically, shizen is traceable to the Chinese word ziran, which points to the spontaneous birth, growth, and transformation of life" (Tucker 161). Daishizen is the path of life, laid out for observation, study, and guidance by the natural world. The fundamental qualities of birth, growth, maturation, decline, and death are modeled in the movements of the seasons as the Earth revolves around the Sun. This cycling occurs on a faster, smaller scale as well -- as the daily rise and fall of the sun in the sky, which guides our patterns of sleeping, eating, working, and more. Great nature does not only imply a nature that acts great, with a meaning similar to "good" or "helpful," but more specifically references a nature that is to be honored and respected. We owe our lives to the details of the universe in which we live: food grows because the Earth happens to be located at just the perfect distance from the Sun; our planet is mostly liquid, which allows us to constantly refresh and clean ourselves; raw materials from the earth give us the ability to fashion tools for weapons and for building homes; etc. Great nature is an all-ecompassing term with multiple layers of meaning, and so it is no surprise to learn that it can also mean the natural, physical world that we live in with all of the various forms of life that we see, from plants and animals to viruses and bacteria. To paraphrase Rev. Koichi Barrish, the movements of Heaven, Earth, and Great Nature encompass all of the transformations, interchanges, and dancing that is going on in the cosmos, from the largest macro scale down to the smallest microscopic level. Human beings are right in the middle of all of this. Daishizen is the infinite spiraling ocean of life as understood to extend from the beginning of our known universe [and before] right down to this very moment in time. The term represents human beings' ability to live in harmony with nature, and any disconnect from this source will lead to personal, societal, and even global illness. In order to tune in to this, we must first develop a feeling of immense gratitude for being alive (Barrish). Nature is our main teacher. It is always self-correcting, evolving, and swinging towards, through, and past a state of equilibrium; and since humans are intimately connected to all of this, we can, and must, adapt and live according to what is called for in each moment. We can learn to do this by paying attention to our diets, practicing meditation, learning to exercise and exert ourselves in varying ways based on the time of year, and of course, by receiving acupuncture and taking herbal medicine. Oriental Medicine is specifically designed to fine tune the various functions of our bodies and minds so that they can work in perfect sync with each other. All of the movements and happenings inside our bodies -- the rise and fall of our chest and abdomen with the breath, extracting nutrition from the food we eat, sweating when we are hot, shivering when we are cold, happiness, sadness, etc. -- are exactly the movements of the universe at large. Daishizen is closely tied to another Japanese term, Kannagara. "The life of man is located in Daishizen, the vast cosmic setting into which we are born, where we live, and within which our lives find any meaning. [Kannagara] is the...spontaneous awareness of...the flow of life... It is a principle of universalism...that calls [humans] back to the roots of basic insight... Kannagara has to do with spirit, and with bringing the spirit of man and his activities into line with...Great Nature. The spirit of Great Nature may be a flower, the beauty of the mountains, the pure snow, the soft rains, or a gentle breeze. Kannagara means being in communion...with the highest level of experiences of life... To be fully alive is to have an aesthetic perception of life, because a major part of the world's goodness lies in its often unspeakable beauty" (Yamamoto 71-72). Great Nature, Daishizen, means living an active life -- not in the sense of physical fitness, but in the sense of taking charge of our own well-being by eating a proper diet, maintaining a good attitude, responding to illness and misfortune appropriately and timely, etc. Many of the lessons to be learned in life deal with spirit, with intention, and with resiliency. Think deeply about the kind of life you want to live. What does it look like? How would your life be if it were awesome? Reach in that direction. Give THAT your energy. All of the above, and more, is in accord with the meaning of Great Nature. Thank you for your time. ~ Clint Cain, LOM Barrish, Rev. Koichi. Facebook. Shinto/Tsubaki America Grand Shrine. www.facebook.com/groups/tsubakishintoshrine Tucker, John A. "Japanese Views of Nature and the Environment." In: Selin, Helaine. Nature Across Cultures: Views of Nature and the Environment in Non-Western Cultures, vol. 4. Springer, Dordrecht, 2003. Yamamoto, Yukitaka. "The Origins and Basis of Shinto." Kami no Michi: The Way of the Kami, The Life and Thought of a Shinto Priest. Stockton, Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America, 1985. Moxibustion, which is often abbreviated as moxa (pronounced, mokusa in Japanese), is the stimulation of acupuncture points with warmth. Moxa goes hand in hand with acupuncture, and in fact, it likely predates the use of needles to alleviate sickness in ancient China. The characters for shinkyu (zhenjiu in Chinese) means "acu-moxa therapy," or "acupuncture and moxibustion." We can see right away that the two therapies are of equal importance. In the Japanese language, mokusa means "burning herb," which tells us precisely what this modality consists of -- burning very small pieces of a dried herb on or near the skin at specific places deemed necessary for treatment. You'll notice that within the field of Oriental Medicine, including this blog, the term moxa simultaneously refers to the treatment modality itself and the herb that is used.

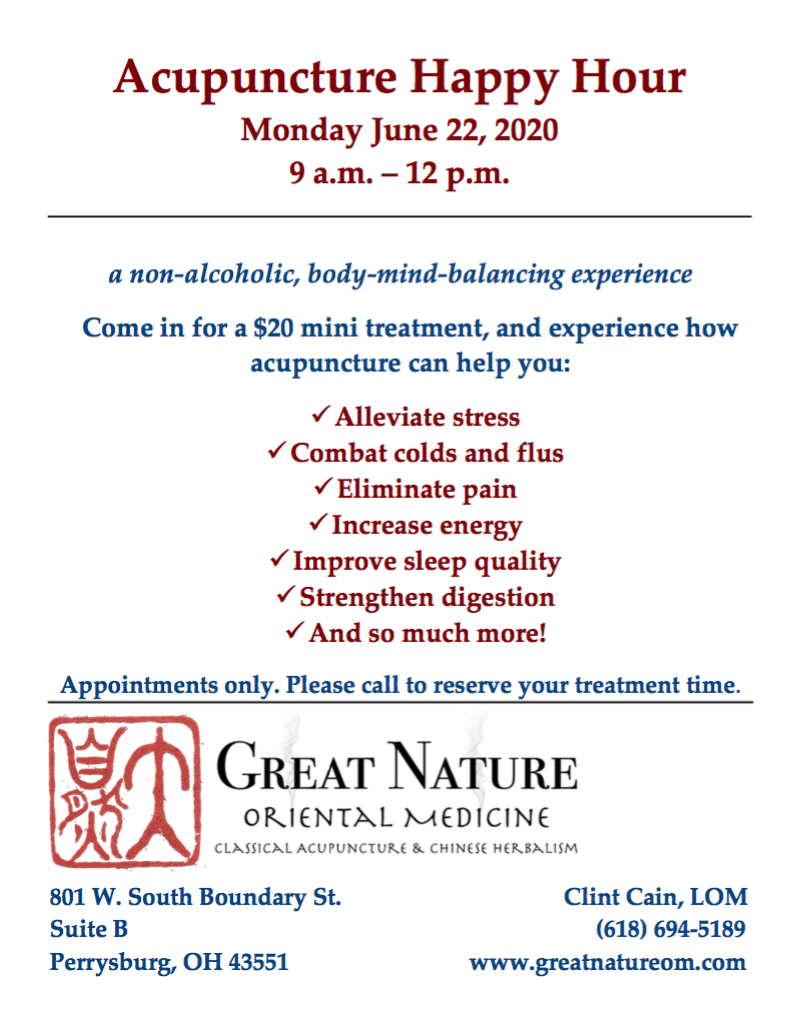

Moxa is performed using a variety of mugwort called Yomogi in Japanese, or Aiye in Chinese. Pieces of this herb are lit and allowed to smolder for a short period of time. There are many different ways in which moxa can be applied, but they can all be placed into one of two categories, direct or indirect. Direct moxa means burning very small cones -- about the size of half of a grain of rice -- directly on the skin. Indirect treatment can refer to placing a piece of moxa on the head of an inserted needle and allowing it to burn, or holding a rolled stick of moxa just above the skin. Whichever method is applied, moxa is a very safe and effective tool to use alongside, or sometimes in place of, the use of acupuncture needles. Yomogi is found in temperate climates of Asia, Europe, and North America. It is a perennial plant that belongs to the daisy family. It has a strong fragrance, and is similar in appearance to chrysanthemum. Yomogi grows to be about four or five feet tall, and it has leaves that are deep green in color, with light brown flowers. The fresh leaves are harvested between May and August, and are then left to dry in the sun before being ground and sifted to remove coarse material. This process is repeated until the desired consistency is achieved. Moxa is graded based on the intended use of the final product. Moxa used for direct, rice grain style application requires more processing in order to yield a more refined, higher quality product; while moxa that is rolled into sticks is often processed less. Premium moxa is aged, yellow in color, and has a fine, fluffy, wool-like feel. At Great Nature Oriental Medicine, we use premium moxa for all applications. Moxa developed in the northern regions of China, where bitterly cold and icy winds prevail. People living in this climate often developed conditions presenting with abdominal fullness, masses and growths, opportunistic infections due to a weakened immune system, musculoskeletal issues, and more. Moxa is used in a wide variety of diseases, including, but not limited to, those just mentioned. Moxa can be used to improve blood circulation, reduce inflammation, stimulate the functioning of the internal organs, relax the sympathetic nervous response, and so much more. In Japan, research has shown that moxa treatments can increase the number of white blood cells, boost immune function, shorten blood clotting time, dilate blood vessels, improve gastrointesinal motility, and enhance liver function, all of which contribute to its ability to relieve pain, reduce stress, and clear congestion and blockages of many kinds. Monday, June 22, 2020 is the next Acupuncture Happy Hour at Great Nature Oriental Medicine. These events are excellent ways to experience the many benefits of traditional acupuncture, ask any questions you may have, and feel awesome in just a short time! Please come in for your $20 abbreviated introduction to traditional acupuncture. This treatment is not intended to diagnose or treat any particular health condition that you may have. It is designed to serve as a general-purpose introduction to the techniques of acupuncture and bodywork offered at Great Nature Oriental Medicine. In order to reserve your treatment time, or for more information, please call (618) 694-5189.

~ Clint Cain, LOM |

This page is intended to serve as a source for links to blogs and articles about acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine that both new and returning patients may find informative and/or entertaining. It is also where I will share information about the history, principles, and benefits of this awesome medicine. Archives

May 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed